New Delhi’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak, in the early months of the pandemic metamorphosing into a public health threat, was that of a strong lockdown. Blanket bans on most sectors, including travel- critical to India’s lifeline, were thrust upon the general public without adequate time to prepare or relocate. Several initial theoretical models predicted that a strong lockdown- akin to that of China’s- would be able to completely curb any form of community transmission. Alternative models proposed that the virus could be tackled with successive lockdowns, each less harsh than its predecessor, with an understanding that it would take a few months more to eliminate the virus from India in totality. As we stand today at the fag end of 2020, we cannot help but ask the question: did a nationwide lockdown help?

In a nutshell, the answer would be yes. General intuition would like us to believe that stronger the lockdown, the better it goes about at saving lives. Yet, data conveys a different tale. To objectively study the impact of lockdowns all across the world, a team of researchers at the University of Oxford assigned a score- called the Government Response Stringency Index– that evaluates the stringency associated with a lockdown for all nations that shut down their economies to avert the pandemic. A higher score indicates that a country has taken stricter measures. It varies between zero and a hundred, where zero indicates the virtual absence of any lockdown characteristic, and its obverse indicating a closure on all fronts. This post is an attempt to deconstruct the lockdown, by assessing the Stringency Index developed as a parameter. If you would like to obtain the specific data-set, feel free to contact me.

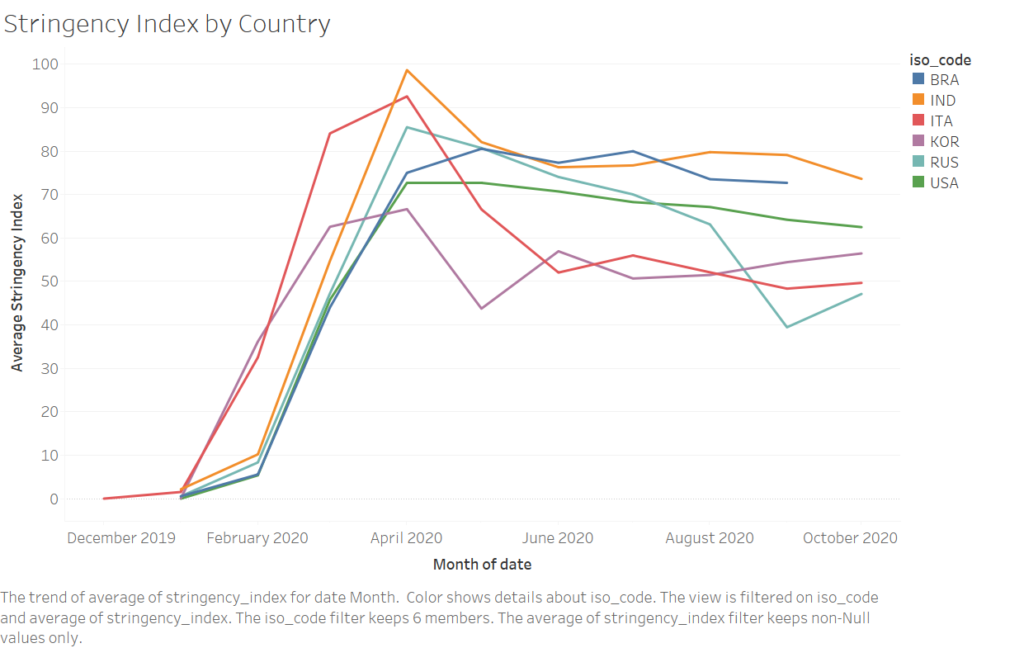

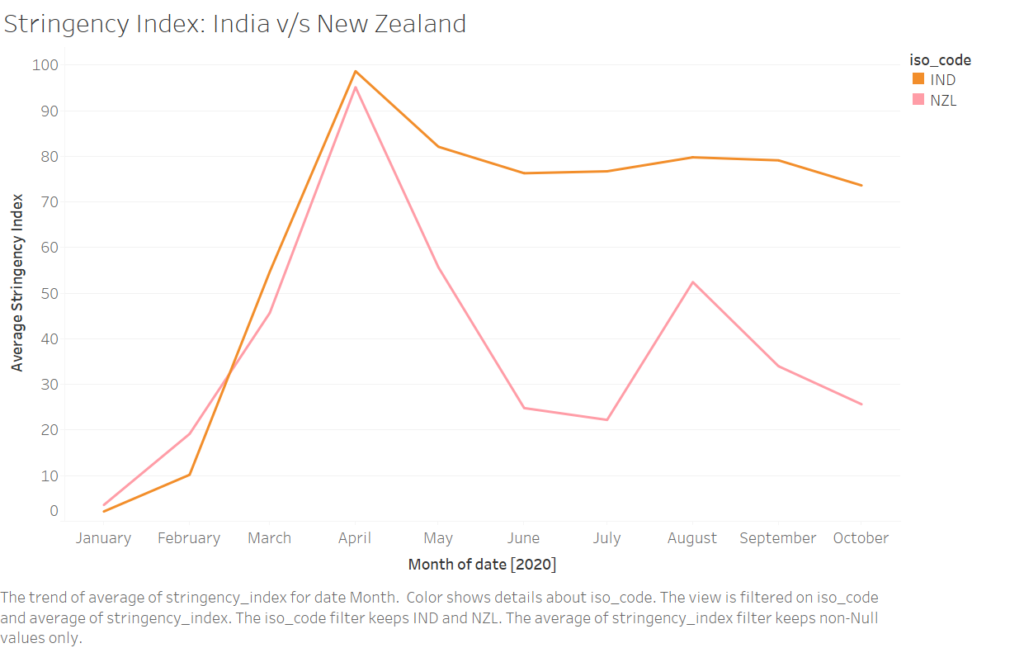

Let us evaluate the stringency index for a select bunch of countries, contrasting them to that of India’s.

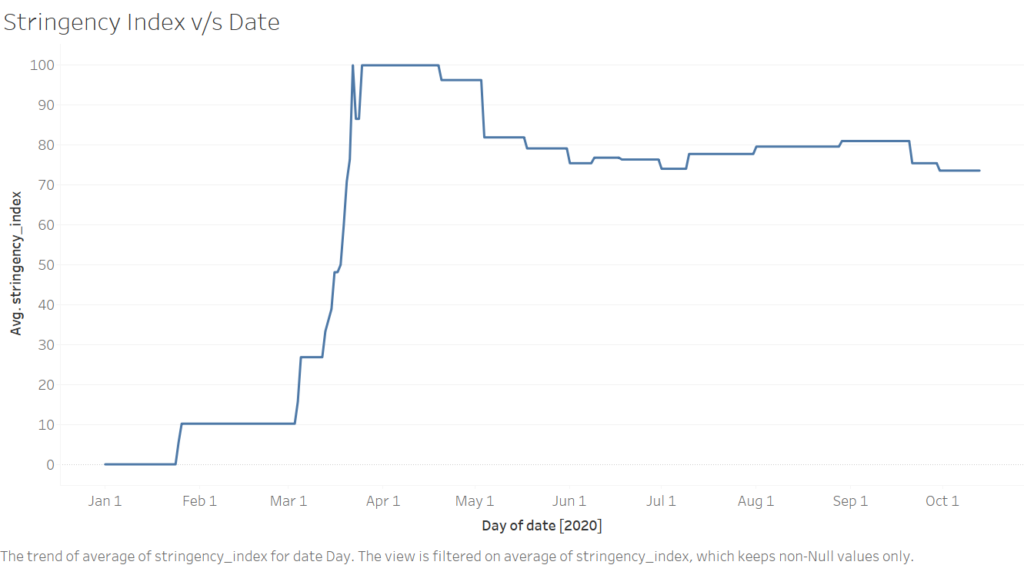

It is no surprise that India on an average tops the stringency index score, nearing a perfect 100 in April. In fact, it even attained a cent per cent score for the days immediately following the announcement of the lockdown. The graphic below, which explores the stringency index value in India on a daily basis, demonstrates the same.

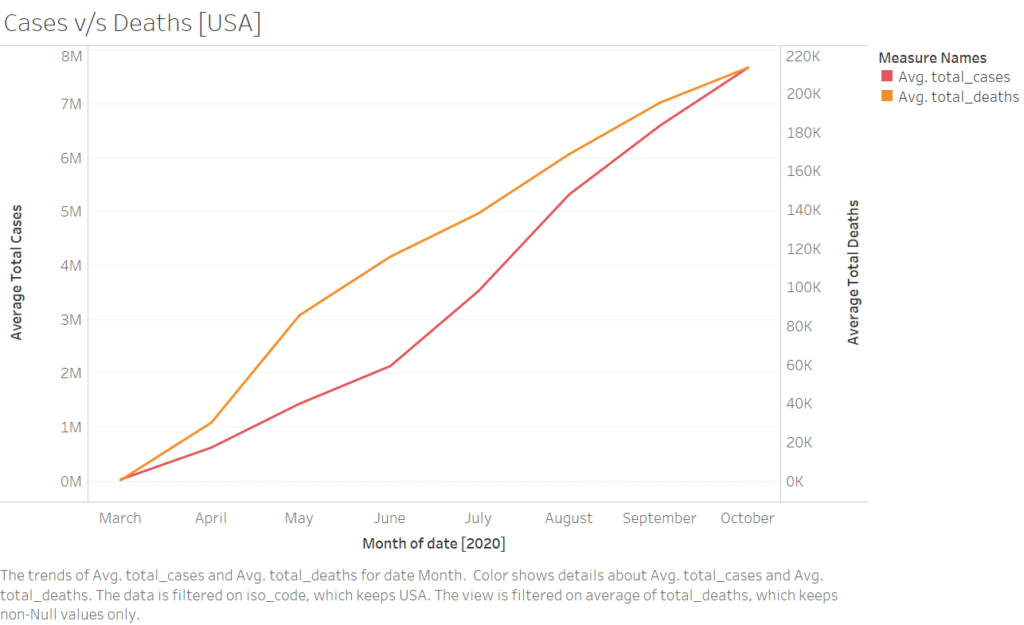

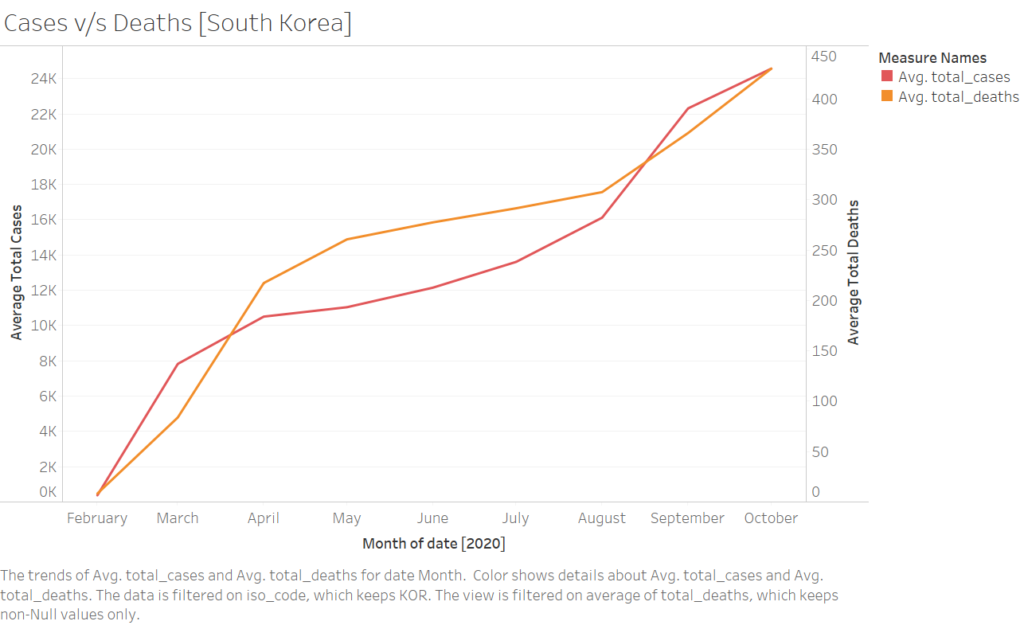

When the onslaught of rising cases strained governmental resources, the priority was shifted onto avoiding deaths. Most afflicted with the original strain of the coronavirus have successfully recovered. The fatality rate has remained low, varying around an estimated 3%. Let us interpret the visual depiction of the same, a contrast between growing number of cases and the number of deaths over time. The plots, made for certain reference countries, will give an idea of how we have fared in our own battle against COVID this year.

(a) India:

(b) United States:

(c) South Korea:

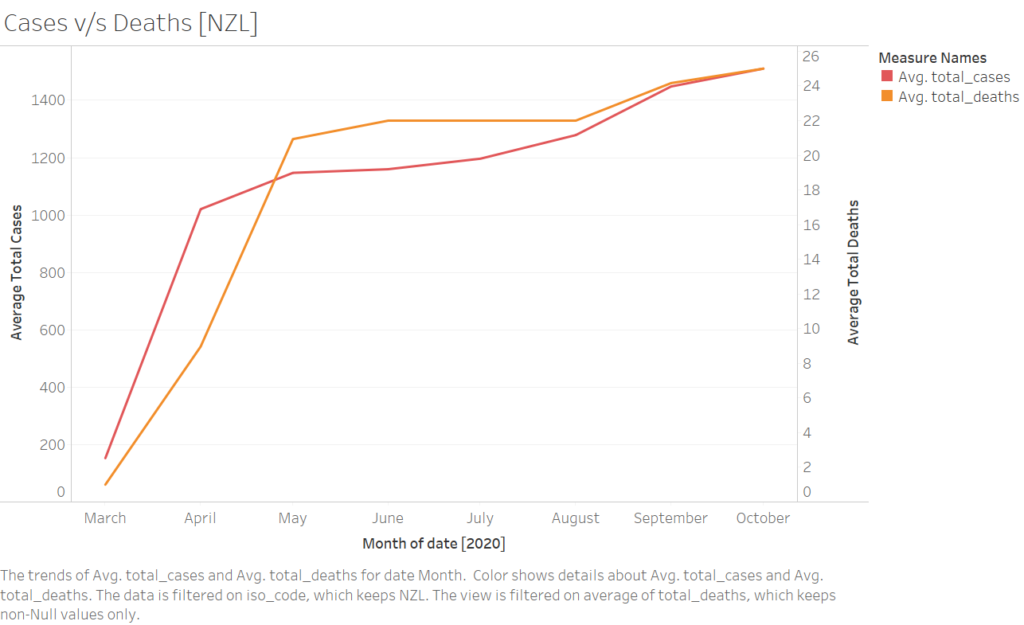

(d) New Zealand:

The flatter the slope for the Average Death trend line, the better a country has performed in terms of saving lives. The right-handed axis represents the total deaths, whilst the left vertical axis denotes the total number of confirmed cases. Observe closely that both India and the United States- two nations with a dubious track record of controlling the burgeoning pandemic- have very steep slopes on both the metrics. Furthermore, the rate of deaths exceed that of the growing tally of cases for both the United States, as well as India. On the other hand, South Korea’s quick response by employing a multidimensional strategy early on, coupled with high-volume testing spared the progressive East Asian state from the brink of a ‘COVID collapse’, if that would be an appropriate way to dub contemporary bleeding economies. New Zealand, under Jacinda Ardern, also deserves a good bout of commendation, having a very low count of both cases as well as deaths. For most part of the year, New Zealand was the only nation that looked to have the imminent threat under control. The graph reveals that from June to August, not a single death was recorded in the land of the Kiwis.

We will further streamline our discussion by taking into picture only India and New Zealand for comparison. By virtue of its effective administration and determination to wipe out the virus from its shores, New Zealand serves as a model state to emulate. But how did it go about achieving such a stellar feat? Here again, the Stringency Index measure will be of great value:

Stringency Index scores for both India and New Zealand mirrored each other till April, beyond that which New Zealand let down its intense vigil while India maintained a hard shutdown. This is part of the reason why India’s economy took such a severe battering, with FY2020-21 Quarter 1 GDP contraction at 23.9%. In comparison, New Zealand’s economy contracted by 12.4%- still a significant figure- and can be attributed mostly to the intensity with which the lockdown was imposed. India’s persistence with the lockdown strategy, both at the Central and at the State level, cost it its economic growth.

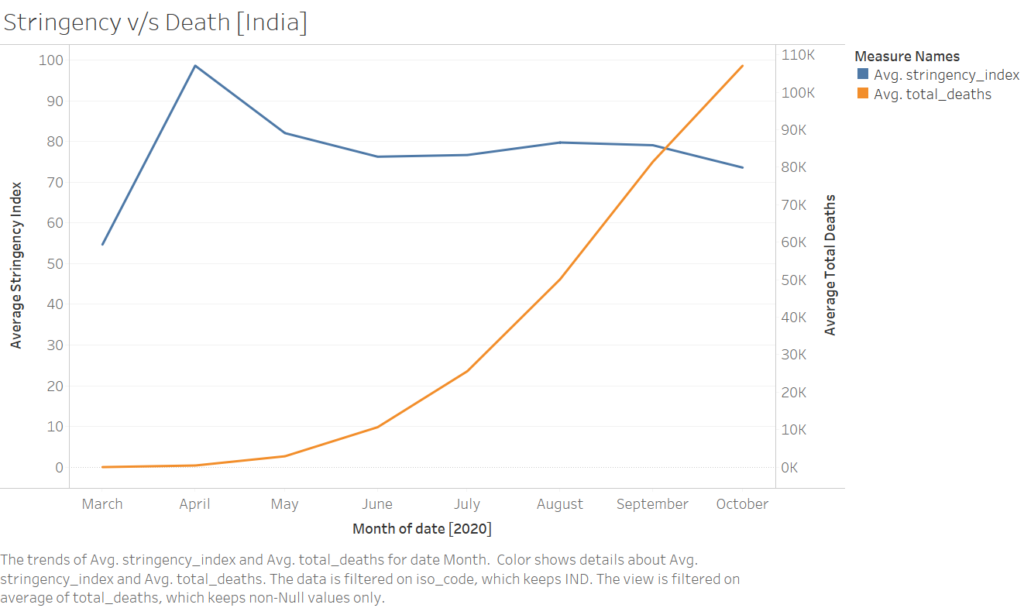

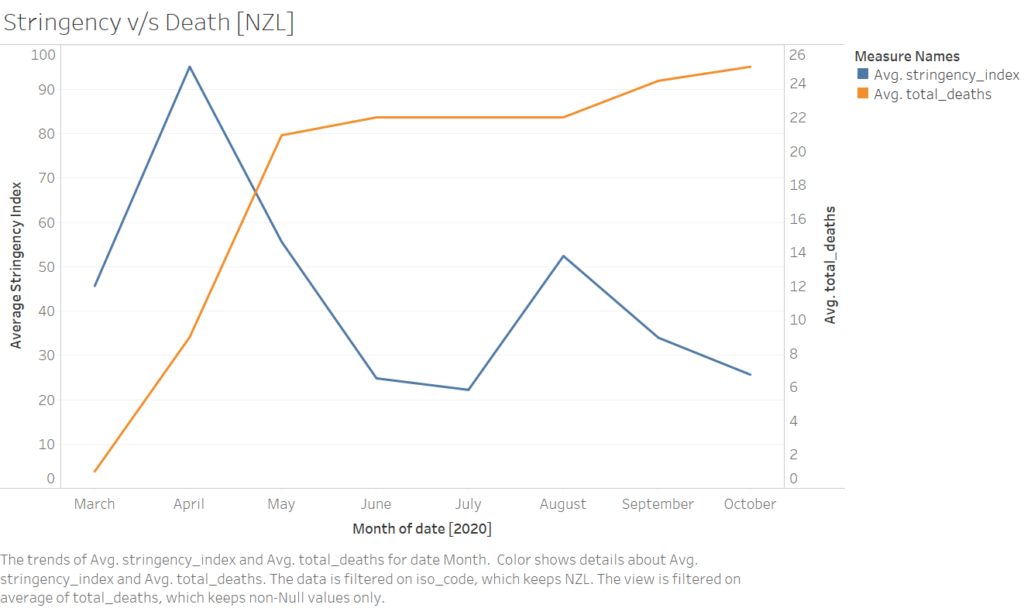

We now come to the most important aspect of deliberation: can stronger containment measures alone save lives? To reason out a answer, we need to plot the Stringency Index against the total number of deaths. We shall do this for both India, and New Zealand.

The difference in lockdown success is beyond compare. If we take India’s case, persisting measures to battle COVID have absolutely been ineffective. So much so, that despite an average stringency index score of 73 in October, our deaths had tallied past 110,000. Worse perhaps, is the rate at which the count of the dead mounted: a near-parabolic growth rate within a span of a few months. New Zealand’s success, made evidently clear by a very low death count of 25 till October, came in the backdrop of it having a Stringency Index of 25 around the same time. This is food for thought for dealing with pandemics that occur in the future: lockdowns alone do not help save lives, but what matters the most in dealing with a pandemic of panaromic proportions as the COVID is how people react and respond to regulations imposed.

A stronger lockdown where people do not obey regulations is, therefore, a waste of national resources. It is much better to bring forth emergency-like laws into action if indeed such relentless measures are to be pursued because it would serve the dual purpose of saving lives and keeping the economy afloat. New Zealand has demonstrated that with responsible living, societal risks can be greatly minimised- and pandemics can quite possibly be exterminated out of their lands.